“It’s going to be very painful for investors.” - Jeremy Grantham, Co-Founder of GMO

What stock market crash do you think that quote refers to? Black Monday? The dotcom crash? The housing crash of 2008? The answer is: the one that is coming next.

The tech bubble is real: The case for

Many investors argue that we are in or are approaching a tech bubble. David Einhorn of Greenlight Capital is one of the most high profile people to raise the alarm bells, stating that while “old” tech companies like Apple are underpriced, several “momentum” stocks cannot come close to justifying their valuations.

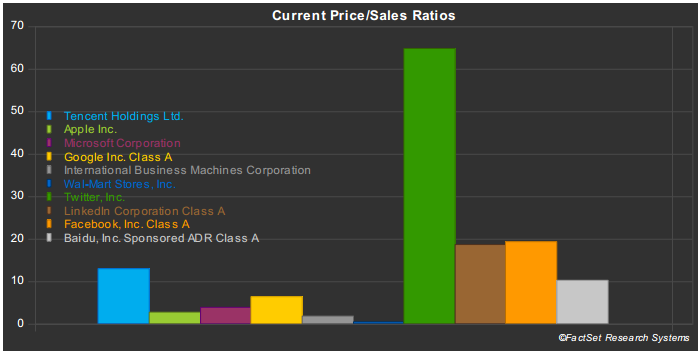

Other observers take note of the fanciful valuations being put on companies that have relatively weak fundamentals. Companies like King Digital, WhatsApp, LinkedIn, and even Twitter have achieved valuations that, under any typical fundamental-based analysis, defy all logic. Twitter, for example, has a Price/Sales ratio currently over 30x, while Facebook carries 15.9x. By comparison, Apple’s P/S is 3.3x. LinkedIn’s P/E ratio is 680x; Google’s is 31x.

The median P/S of companies within FactSet’s Internet Software/Services sector that have revenues over $500m (which includes companies like Google, Facebook, Baidu, Tencent, and Yahoo), is 2.4x. The standard deviation of P/S ratios across this same sample (58 companies) is 5.1. Compare this figure to the standard deviation of P/S ratios in other sectors such as Consumer Services (1.5), Transportation (1.4), and Communications (1.5), and you start to see the difficulty in accurately valuing these businesses.

One of the hallmarks of the dotcom crash was investors abandoning proper fundamental analysis of companies in favor of pursuing growth of user base, and many of the IPOs we see today have the same hallmarks.

How is it that a company that has no revenue and no unique IP in the form of WhatsApp can be worth $19bn? Zynga, the online game-maker, posted a Q1’14 loss of $61m, and it currently trades at less than half of its December 2011 IPO price. So how does King Digital achieve a $6bn valuation on the back of revenues that are almost 80% reliant on Candy Crush? Quora, a question-and-answer website with no revenue, earlier this month took $80m from venture capital investors just to keep it in the bank. The most recent company to hit the headlines is Uber, the car-hire app, which has just accepted investment at a valuation of $17bn. Of course, if Uber achieves everything it hopes, then $17bn could well turn out to be a bargain, but what if it doesn’t?

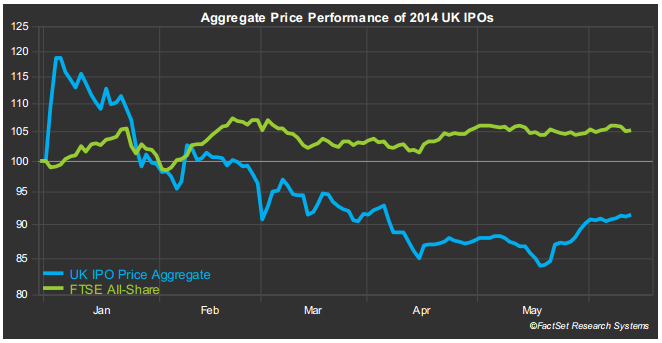

Aside from this, even outside the tech sector you need only to look at the sheer volume of companies looking to tap the market’s appetite for new equity to see that the tides are rising. In the UK, FactSet shows that there have been 57 new listings on the London markets (Main and AIM) between January 1 and May 31, 2014. The number for the same period last year was 24.

Of these IPOs, 25, or 44%, are currently trading below offer price.

Does this mean we are in a bubble? No, but it does show that investors have reservations about the ability of many of these companies to deliver value. It also means that lower quality businesses are entering the market, with investment banks talking up businesses to an extent that fundamental analysis simply does not support.

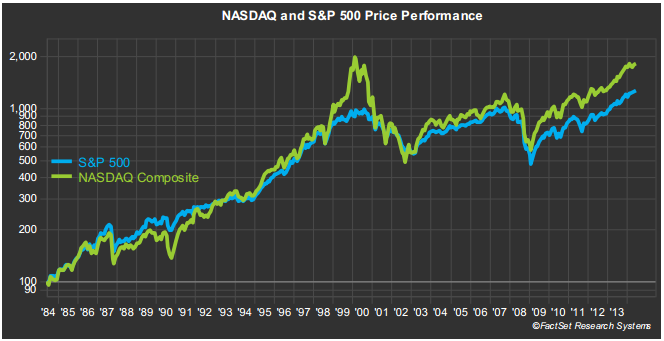

In predicting a bubble, another oft-cited factor is the rising price of the NASDAQ. It might be below its 2000 peak of 4698, but not by much. It currently sits at 4333, having risen 136% in five years and 27% in the last 12 months. At the current rate of growth NASDAQ will surpass its previous peak before the end of 2014. The S&P 500 has grown 21% since this time last year.

What bubble? The case against

Market bulls argue that we are not in bubble territory; there is nothing to fear just yet.

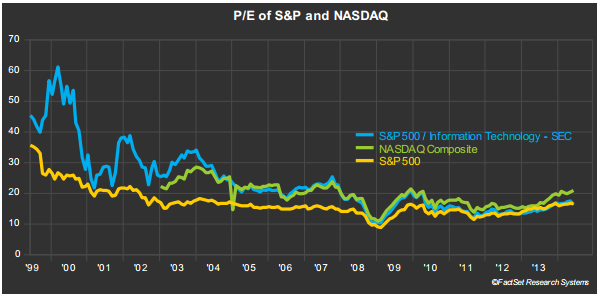

According to them, U.S. stocks are actually relatively good value (i.e., the P/E ratios are lower). If we look at the NASDAQ and S&P over the last 15 years or so, we can see that the P/E ratios have, removing the anomalies of the 2000 peak and 2008 crash, been fairly steady. The S&P 500 Information Technology sector currently sits at 16.6x on a last twelve months basis. Its 15-year average, including the peak and crash? 16.8x. The NASDAQ’s current P/E of 20.9 also sits relatively well against its average since 2003 of 19.5. It’s the same story when we look at Price/Sales. So we have some way to go before hitting the fantastical heights of previous eras.

The other key argument that market-defenders lean on is the fact that during in the dotcom crash, there was a hysterical investment attitude from not just institutional investors but “every mom and pop investor and every cabdriver and every shoe-shine boy” (Marc Andreessen, Venture Capitalist). There is none of this at the moment. Appetite is being driven by long periods of low interest rates, forcing investors to seek returns in more risky ventures such as startups and junk debt. Moreover, private equity and venture capital firms who a) have been sitting on piles of cash for years, and b) are desperate to offload long-held portfolio companies into the willing arms of the market contribute both supply and demand. Add to this the phenomenal growth rates of some of these tech companies (in terms of user base and popularity, if not profit), and you have a potent cocktail for investors.

So, are we in a bubble? Is the market on a precipice? A subset of technology firms is exhibiting bubble-like behavior even if the term cannot yet be applied to the wider market. Not all of the firms currently riding the tech wave can succeed; indeed, most won’t in the long term. Firms like Twitter and LinkedIn face a huge challenge trying to elicit payments out of users, many of whom would instantly turn away should they face paying fees. The likes of Uber and AirBnB have different challenges, facing the wrath and pressure of regulatory and political opponents. Some of these hurdles may be too big to jump.

What’s to be done, if anything? Surely it’s better to recognize a bubble BEFORE it reaches the peak, so that we can prevent broader damage to the economy by scaling back practices that exacerbate the problem. Hopefully, this time is different. Hopefully, investors have gotten wiser over the years. Hopefully, England will win the World Cup.

What do you think: are we in a tech bubble?