With all the chaos surrounding miscalculated net asset values in ETFs and mutual funds, it might be smart to understand what NAVs are and why they do—and don’t—matter.

Imagine you were making the very first mutual fund. You and your best friend each put $10,000 into a brokerage account, and you agree to hire Bill & Ted’s Excellent Investors (BTEI) to run the money for you. You agree to pay BTEI 1% to take care of it all.

But how do you actually keep track of everything? You could just share the login to the brokerage account and figure that since you went in with equal amounts, you were entitled to half of the balance. But what happens when you want your money out? Or you want to add more? Keeping track of your ownership stake gets tricky fast.

That’s where the idea of unit-based accounting comes in. Instead of just keeping the account in one big dollar amount, we decide that our new fund will issue 100 shares when we launch it. Since we’re putting in $20,000, each share will be initially worth $200.

Now, if we want to see how we’re doing, all that we have to do every day is take the pile of money in the account, divide it by 100, and we have a per-share value. Simple, right?

The good news is that the structure is really just about that simple. Every fund has a custodian. That custodial account holds all the assets of the fund, and also records any structural liabilities (like, being short a stock).

In principle, this is all an ETF or mutual fund net asset value is. It’s a unit of measurement. But there are issues and rules about each one of the words in “net asset value.”

Let’s start with “Net.” NAVs are net, in the sense that they are the sum of all of the assets in the account, minus all the liabilities. But there are things not necessarily obvious that have to be “netted” to. Someone has to keep track of how much money we owe Bill and Ted. Someone has to keep track of any expenses (like paying the custodian). In addition, things like dividends you’re owed or paid can complicate the calculation.

Because of all this netting, the role of calculating this is considered an entire separate job: fund accountant. Many custodians simply do this in-house using proprietary software and dedicated employees. Some outsource it or use third-party software vendors.

Next up on the opportunity for confusion is “Asset.” This would seem very simple: The fund either owns something or it doesn’t. Unfortunately, the mutual fund industry is governed by an 80-year-old document called the Investment Company Act of 1940. The specific rules for what counts as an asset include this little-known fact (from Rule 2a-4):

“Changes in holdings of portfolio securities shall be reflected no later than in the first calculation on the first business day following the trade date.”

What that means is that if, at 9:30 this morning, BTEI decides to sell all of its Apple stock and buy IBM instead, that trade will not actually be reflected in the pool of assets used to calculate total value at 4 p.m. tonight. If Apple were up and IBM were down since that opening trade, the investor won’t actually experience the pain of IBM’s decline until tomorrow’s NAV. This means that in a very real sense, the NAV of a fund on a day that involved a single portfolio transaction is a fiction.

Put another way, NAV is yesterday’s portfolio processed with today’s prices. This fiction can and does lead to real distortions in performance statistics (there’s a great 2006 paper on the subject essentially proving it.)

But where the ambiguity in NAV really happens is in the word “Value.” Fund boards have the responsibility of establishing a set of rules about how any security in the fund will be valued. Most of the time, this is trivial—it’s pretty easy to get the closing price of IBM. But in many cases, reasonable people can disagree.

What if a security hasn’t traded recently? Do you use the last traded price if it’s two days old? What about bonds, which rarely have an “official” price? And how do you handle valuing securities that are trading in Asia, with no overlap to U.S. trading days?

Every firm has a completely unique and undisclosed set of rules for how to answer all of these questions. There are some conventions—most fund companies use bond pricing services, for example, to independently mark their bond prices. But many times the differences are enormous.

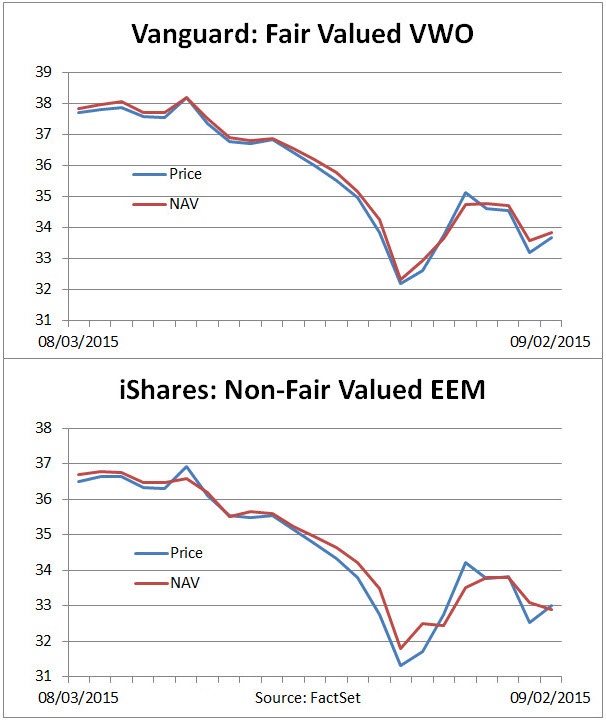

Vanguard, for example, uses a “fair value” for stocks in, say, Japan. So if Japanese futures and U.S.-listed Japanese stocks rally like crazy during U.S. market hours, they will use a formula to adjust last night’s closing prices for Japan to reflect the new information. For ETF investors, it’s normal for a fair-valued ETF to look like its trading closer to fair value than a nonfair-valued NAV, but your actual holdings can be identical. The poster children for this story have been emerging market ETFs from Vanguard and iShares:

It’s almost impossible to know whether an ETF or mutual fund is fair-valuing its NAV, and, in fact, some fund companies only fair-value on occasion. Which ultimately means that you, as an investor, simply have to trust the fund company and its accountant is doing something prudent.

Thankfully, 80 years of doing this means best practices are pretty well established, whether an ETF or mutual fund fair-values or doesn’t fair-value.

Once we have a final number that represents the total true value of the fund based on all of the rules and policies, we just need to know how many shares to divide it by to get the number we call NAV.

That’s where the transfer agent comes in. When a new investor wants to join our fund, a transfer agent issues newly manufactured shares and writes down the investor’s name. When the investor wants out, the transfer agent hands them back cash and destroy the shares.

In mutual funds, this is generally done in cash, and mom-and-pop investors have lines on the transfer agent’s books with their name and phone number and all sorts of other information on them.

In the case of ETFs, that creation and destruction of shares is done only by authorized participants, and generally in-kind, but the same thing happens: The transfer agent makes or destroys shares and keeps track of the totals. And since the rules state that fund accountants always look at yesterday’s holdings, they apply the same rule to the share totals.

So you take the big portfolio value number, divide it by the number of shares and you have a net asset value. What then?

If you’re a mutual fund investor, your NAV is an incredibly important number, because it’s your actual price. When you buy or sell a mutual fund, you put in an order in the middle of the day, and you get your actual buy or sell executed by the fund company at NAV.

As an ETF investor, it’s hard to come up with a reason to care overmuch about the precision of your NAV. Obviously, all else equal, you’d like to know exactly how much your investment is worth, and certainly the authorized participants who are arbitraging-out price discrepancies between market prices and fair value need a fair value to arbitrage against.

But the reality is, nobody in the process actually uses NAV. They don’t even use the intraday value calculated and disseminated every 15 seconds by the exchange. Instead, they build their own estimate of what they think the basket of securities a fund holds is worth, and arbitrage against their pricing assumptions—not those of the fund companies.

As an ETF investor, what you should care about is your price—the actual traded price at which you buy and sell. NAV—and particularly intraday NAVs—can be useful to ETF investors as a reference to set limit orders, and to know if you’re generally getting a fair deal. But your actual experience is entirely based on market prices. So while it’s not great that one fund accountant (Bank of New York, leaning on SunGard’s fund accounting platform) had a major hiccup and had to restate some NAVs in late August, it’s also largely irrelevant to you as an ETF investor.

How Private Capital Is Powering the Johor-Singapore Special Economic Zone

This FactSet analysis provides insight into the early stage of the JS-SEZ progress with key data points. Stay informed on how...

How Transaction Cost Analysis Is Evolving from Compliance Tool to Trading Decision Support

Discover insights to further strengthen your TCA capabilities in this FactSet analysis. Consider how you can make the most of TCA...

The information contained in this article is not investment advice. FactSet does not endorse or recommend any investments and assumes no liability for any consequence relating directly or indirectly to any action or inaction taken based on the information contained in this article.