By Anthony Garcia | January 29, 2015

Corporations thus far have put up resistance to the shareholder demand for proxy access, where holders of a certain ownership level for a certain time period will be allowed to include their own director nominations on the corporate proxy. In fact, at least 18 companies recently submitted no-action letters to block shareholder proposals for proxy access. The SEC announced on January 16, 2015 that, after direction from Chair Mary Jo White to review the application of Rule 14a-8(i)(9), the Division of Corporate Finance would no longer express any views (either granting or denying no-action requests) for the 2015 proxy season under this exception.

But proxy access may be much more than another checkbox on the shareholder rights scorecard. It is a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

General acceptance of proxy access could allow activists to pool resources, ally with institutional investors, and take over entire boards in a single year and without the warning of even a single 13D. Although such a situation may require significant activist coordination, matching the activist campaign demands to institutional investor or proxy advisor perspectives, and no further SEC intervention or tightening of regulations, all of the ingredients are present and proxy access may be the catalyst to set off this type of chain reaction.

The proxy access demands coming from shareholders are calibrated to a standard 3% ownership level held for three years prior to the submission of a nominee to be included on the corporate proxy. The proposals typically include that nominations can only be made for 10-25% of the eligible director seats, or a minimum number of seats depending on current size of the board. A plain language interpretation of the boilerplate language lends itself to the interpretation that any eligible shareholder may submit nominations and, thus, multiple eligible shareholders may submit nominations. If multiple shareholders all nominate different directors and all those directors appear on the corporate proxy voting card, then shareholders would have the opportunity to vote for a board that consists of shareholder proposed directors above the stated nominee proportion and up to 100% of the board seats.

The corporation may seek to limit the activists to a single slate of nominees, but the standard proxy access proposal differentiates between the shareholder or group (“nominator”) and the candidates (“shareholder-nominated candidates”), and only guidance from SEC with regard to “group” status is filing requirements under Section 13(d)(3). However, the tight standards of the “group” requirement have allowed multiple activists to participate in a campaign without formal group recognition. Given that past court cases concluded that investors offering a joint slate of directors was not sufficient to make them a “group,” it is unlikely that independent 3% owners each offering its own slate of directors would be given a group designation limiting the shareholder-nominated candidates collectively to the specified percentage of eligible director seats.

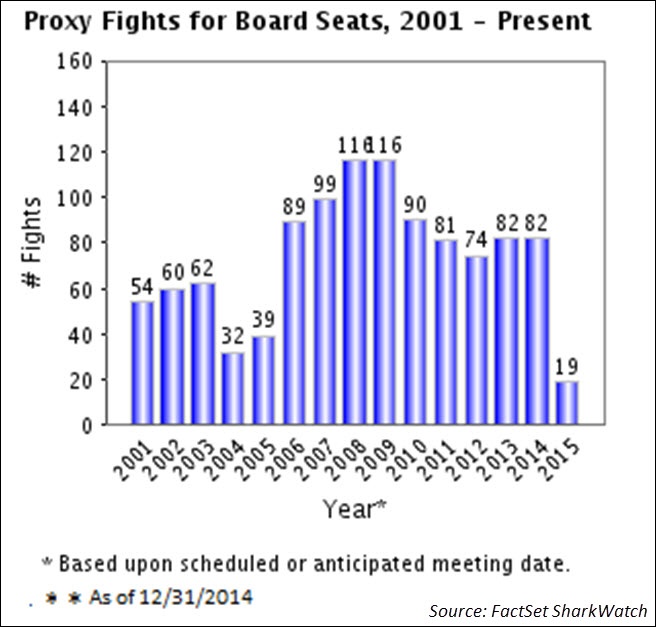

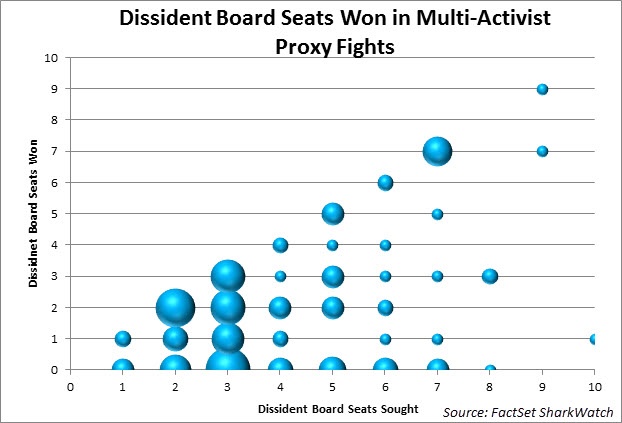

This type of “wolf pack” tactic is now a headline topic, but FactSet has tracked 46 campaigns dating back to 2003 that involved multiple parties but no 13D filer—whether individually or as a group. In 34 of those campaigns, the dissident group sought at least one board seat, and the group succeeded in 14 campaigns. In six of those campaigns, the dissident sought multiple board seats and won all of the seats.

A comprehensive list of wolf pack tactics is impossible to identify given the informal nature of the arrangement, but tracking activists that have jointly filed as a group in prior campaigns, nominate each other for board seats, buy or increase positions in a target company after the announcement of a campaign, or target similar types of companies and strategic goals may highlight potential allies hiding among the 1-5% owners.

From 2001-2014, FactSet identifies 405 campaigns where multiple parties were involved in a specific campaign. The cooperation among the parties could be as a joint 13D filer, where the dissident used another activist manager on the dissident’s director slate, or where the activist held a significant position in a company and supported the campaign. Of those campaigns, 175 included at least one member of the FactSet SharkWatch 50 in the group, which suggests that the tactic is not limited to activists without the capital and resources to follow through on their own campaign. For example, Barington Companies Investors LLC has been involved in 39 total campaigns since 2003, and in 26 of those campaigns there was a second party associated with the campaign, including SharkWatch 50 activists such as Starboard Value LP (16); Clinton Group, Inc. (2); Millennium Management LLC (2). Starboard, which itself has over $2.1 billion in equity assets, was one of multiple parties in eight additional campaigns, including three campaigns where Knightspoint Partners LLC was involved and one that included Sandell Asset Management Corp.

Of all the campaigns involving multiple parties since 2001, 220 included the dissident group seeking board seats and 107 included the dissident winning at least one board seat, 84 of which were triggered by a proxy fight.

Since 2001, SharkWatch 50 activists with over 10 campaigns either as part of a group or in a multi-party campaign include: Barington Companies Investors LLC (26); Bulldog Investors LLC (15); Lone Star Value Management, LCC (11); Starboard Value LP (24); Steel Partners, LLC (13); and Western Investment LLC (37).

Going back to proxy access, formal group efforts may be an even greater threat than wolf packs because three 1% shareholders could form a group and look to immediately submit a group slate of shareholder-nominated candidates, assuming each member held their respective position for three years. The current proxy access proposals are silent with regard to the group having a formal status or being recognized as a group for the entire duration of the individual group member’s ownership. The companies may not have the advance notice that it is assumed from the three-year ownership provision. Companies may need to include language similar to the Whole Foods proposal, which permits “any shareholder (but not a group of shareholders)” proxy access under the company criteria of 5% ownership for five years. Many companies are relying upon the Whole Foods no-action letter, which was granted on the basis of the proposal conflicting with management’s proxy access proposal, including Cabot Oil & Gas (5% for three years); Arch Coal and Marathon Oil (5% for five years and single shareholder); eBay (5% for four years); First Merit (5% for three years and no groups greater than 10 shareholders).

Although such coordination may appear to violate insider trading rules, the information is often freely disseminated by the dissident and there is no breach of a fiduciary duty. With the ability of a dissident to reach a large audience and the SEC no longer serving as a proxy censor, wolf pack and formal group campaigns may solidify organically as information is shared. Starboard Value issued 14 press releases and a 300-page report on its critique of Darden Restaurants, and its public tactics gained sufficient support to win all 12 board seats at the 2014 shareholder meeting, including support from often-allied Barington whose prior campaign to break apart Darden had failed; Third Point won three seats on Sotheby’s board with support from Marcato Capital Management; PetSmart sold itself to a private investor group under pressure from Jana Partners and Longview Assets. These are just some of the high profile examples of activists joining together on campaigns as the growing number of activist-driven funds increases and list of potential value-driven investing opportunities dwindles.

AI Fear and Insurance Stocks Revisited

Stay ahead with FactSet’s weekly insights on the latest insurance industry updates, trends, events, and market developments.

Capturing Megatrends: A Data-Driven Approach to Thematic Investing

Explore how data-driven thematic investing captures megatrends like AI and demographic shifts. Learn how to identify quality...

U.S. ETF Monthly Summary: February 2026

Explore U.S. ETF trends with FactSet's monthly summary. Get flow stats by asset class and sector, ETF launches, and this month a...

U.S. Mergers & Acquisitions Monthly Review: January 2026

Explore FactSet's U.S. Mergers & Acquisitions Monthly Review. Gain deep insights into market trends and expert analysis to inform...

The information contained in this article is not investment advice. FactSet does not endorse or recommend any investments and assumes no liability for any consequence relating directly or indirectly to any action or inaction taken based on the information contained in this article.