Why do companies opt for a spinoff? The most common reason is to maximize shareholder value by breaking up an entity so separate units can operate without hindering each other. These deals are essentially failed transactions, because no buyer was found, and the parent is forced to give the business away and let shareholders decide where they want to invest.

Reviewing the spinoffs covered in FactSet M&A, where we have enough pricing data for both the "Spinner" and the "Spinco," let's take a look at the 300+ deals in the last 10 years that passed our filters and pay homage to awards season by seeing "who wore it better."

The Red Carpet

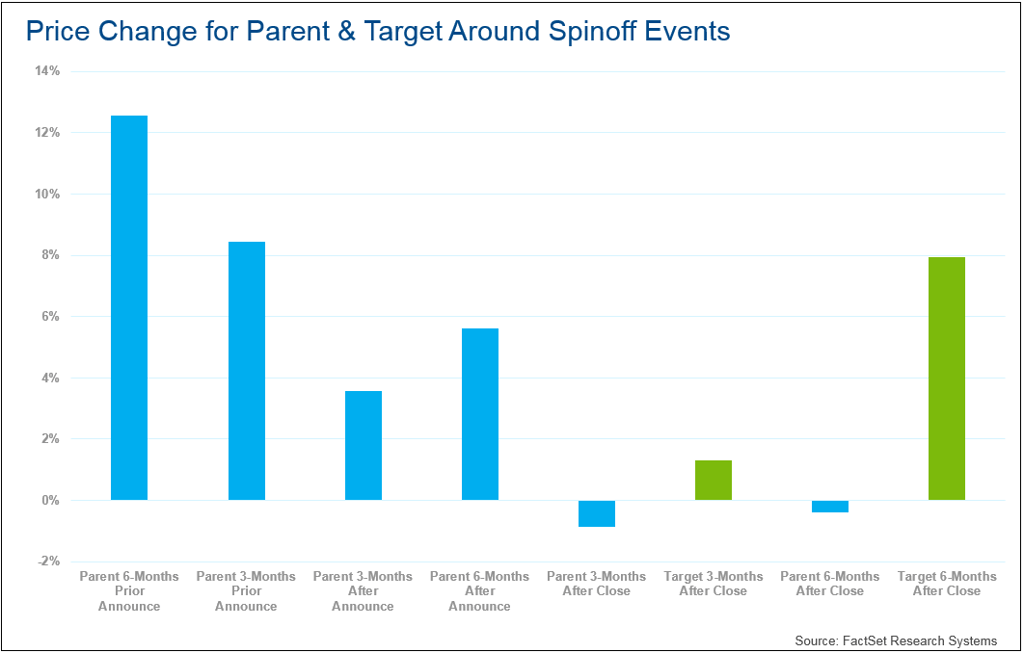

First, just looking at the returns for the parent company, you can see that the price return six-months prior to announcement is a healthy 13%, and even 8% just three-months prior to announcement. Additionally, after the deal closes, the data shows that the parent company performs much worse than the spinoff company. Maximizing shareholder value appears to be directed almost entirely at the spinoff company rather than the parent. Perhaps the real comparison is against a peer group or against a benchmark, but certainly some further analysis can uncover additional insight and value.

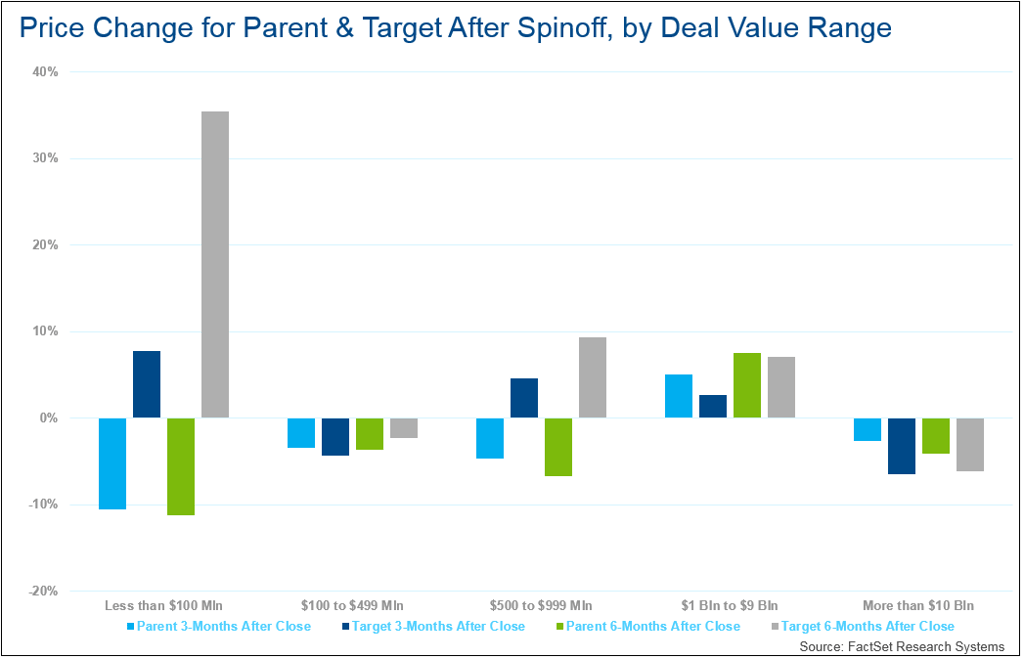

Second, breaking it down by value, the target significantly outperforms on deals under $1 billion and lags slightly on the larger deals. Worth noting is neither has a positive price change three- or six-months after closing. Perhaps here, an additional comparison should be made against the market cap of both companies, to see the relative size of each under the premise that mega-cap companies perform at the benchmark or in-line with the greater economy and have challenges growing faster.

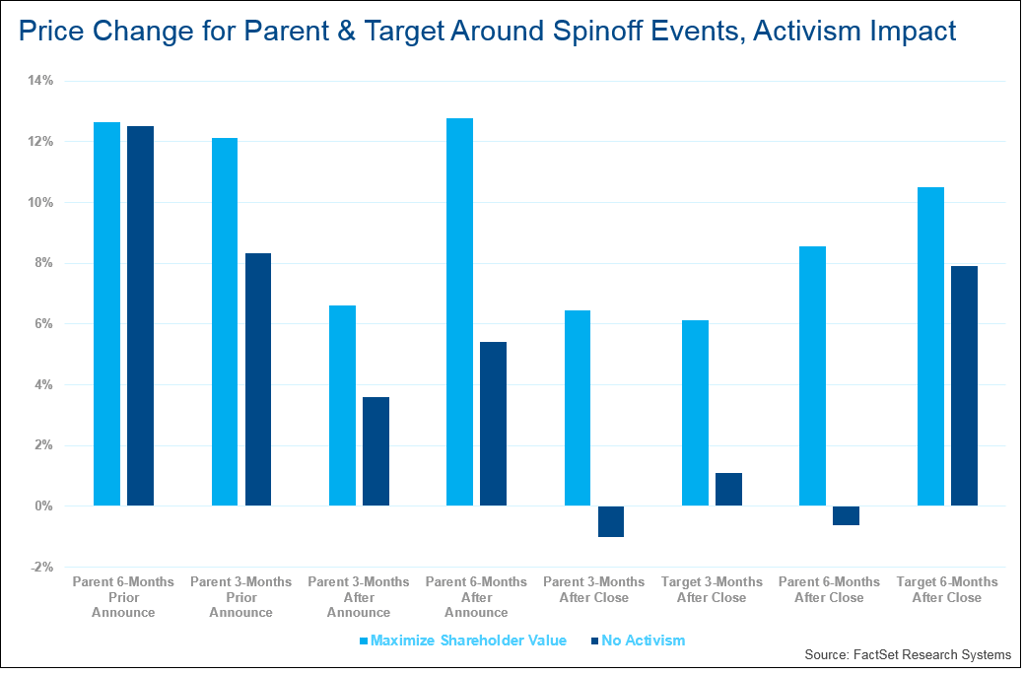

Finally, we can see if corporate activists acted as the trigger for any spinoffs, again looking to maximize shareholder value. Looking at the activism history for the parent companies, there are six instances where there was an activist campaign looking specifically to maximize value within six months of the spinoff announcement. You can see in the chart that spinoffs that had prior activists led to higher returns, though after six-months the target still outperformed the parent.

This suggests that activists may fit the criticism that they are just after short-term results. However, it is clear that in transactions with activism, both the parent and target perform better than those without, and the target consistently performs better than the parent six-months after closing.

In an example of this recently, BHP Billiton has come under scrutiny by activist Paul Singer’s Elliott Management, arguing for a spinoff of its U.S. petroleum business into a separate company. BHP is poised to fight the proposal, but other shareholders may also want to review the history of spinoffs with activists.

More analysis can certainly uncover more value, but based on this limited review it seems that the spinco is usually the better dressed post-deal.