Fears of regional weakness—economic slowdown in China, the shock of devalued oil to OPEC, recessions expected in Argentina and Brazil—are driving volatility across the global investment universe. Though these concerns are often labeled with specific nations, the market has long accepted that there’s hardly such thing as a crisis limited to one country.

Unfortunately, though, conventional tools do little to illuminate and quantify answers to even basic questions with regard to geographic risk: where specifically are we exposed, and to what extent?

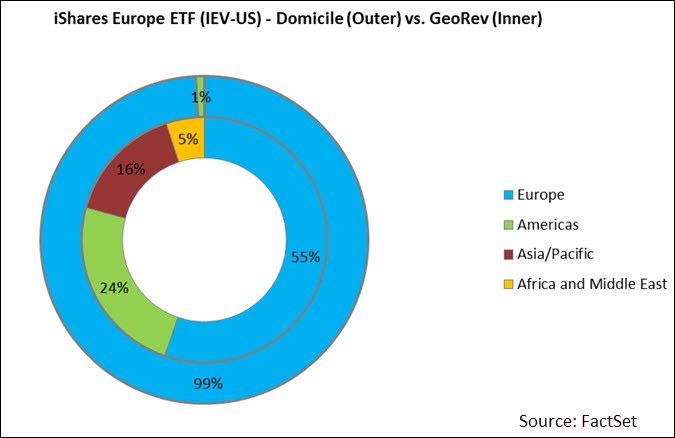

If we look at the iShares Europe ETF, for example, we would gather little intelligence by learning that approximately 100% of the fund’s holdings are domiciled in the European continent. However, a closer look at individual geographic segment disclosures provides added insight and reveals that little more than half of the holdings’ revenues are actually derived from the nations of Europe.

Search Results for China Revenue… “Did you mean: Rest of World Revenue?”

Even with the knowledge of geographic segments, aggregate exposures and developing trends can be difficult to uncover in large portfolios, watchlists, or funds. Individual security analysts have time to model these disclosures, but the task of overseeing multiple companies would require significant resources. Even a team that could manage the filings of dozens or hundreds of securities still must make sense of idiosyncratic regional disclosures. Apple, for instance, provides a breakdown of revenue earned in “Greater China,” but, in its 2014 10-K, Google carved the planet into only three geographic regions: the United States, the United Kingdom, and “Rest of World.”

To address the work of normalizing these disclosures, we use FactSet Geographic Revenue data, which estimates sources of revenue that aren’t explicitly expressed, opening the door to comparability within a universe of companies.

Simpler and More Accurate Research in Aggregated Geographic Risk

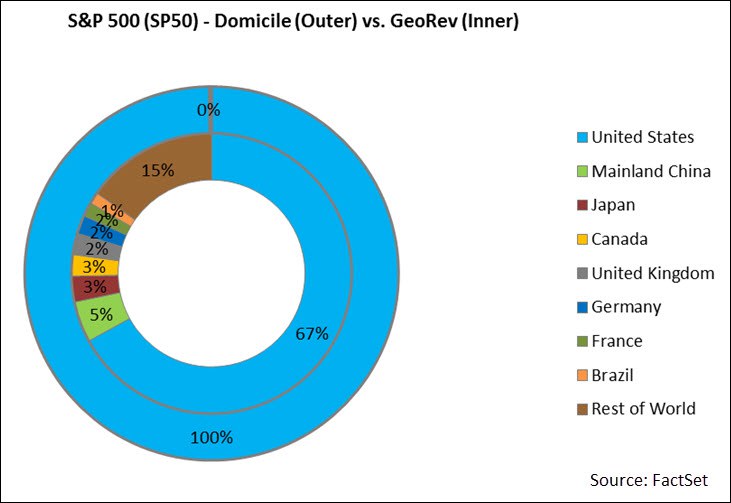

The competitive landscape is continuously evolving, but each niche of the global market has its own story to tell. In the S&P 500, for example, one third of revenues are generated outside of the U.S.

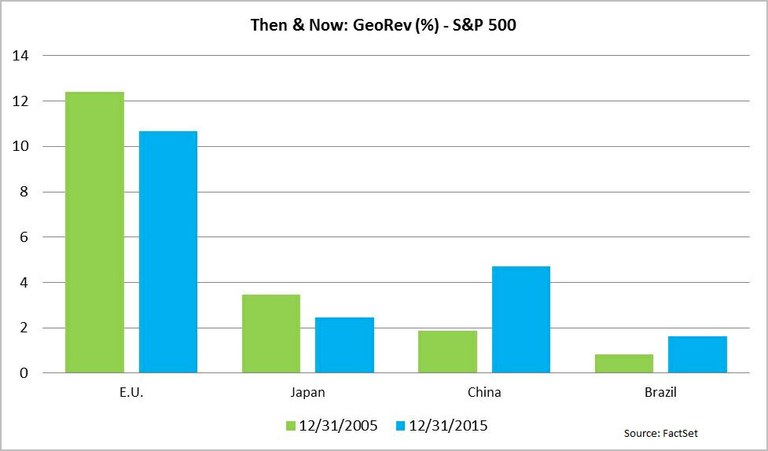

Here, the growth of emerging economies is a well-reported phenomenon. But to quantify the extent with which the market share of old stalwarts like Europe and Japan has fallen in favor of rising powers like China and Brazil provides new insight.

How Can a Fund Be “Ex-U.S.” Anyway?

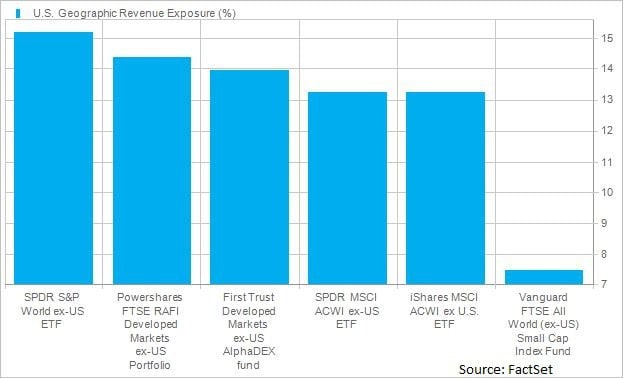

The value of this dataset is especially apparent for geographic investment strategies. Many funds claim to focus investment—or minimize exposure—to particular countries or regions, but how well do they accomplish this goal?

For example, an investor with concerns of overvaluation might look to “ex-U.S.” funds for safety. If only it were so easy to fully exclude a country with such a broad reach. Several large “ex-U.S.” ETF options only reduce U.S. exposure to as low as 13 percentage points.

However, an investor could further limit unwanted geographic risk by focusing on smaller equities and those with locally-supported industries. For example, the Vanguard FTSE All World ex-US Small Cap Index Fund has half the U.S. exposure of other headline “ex-U.S.” funds.

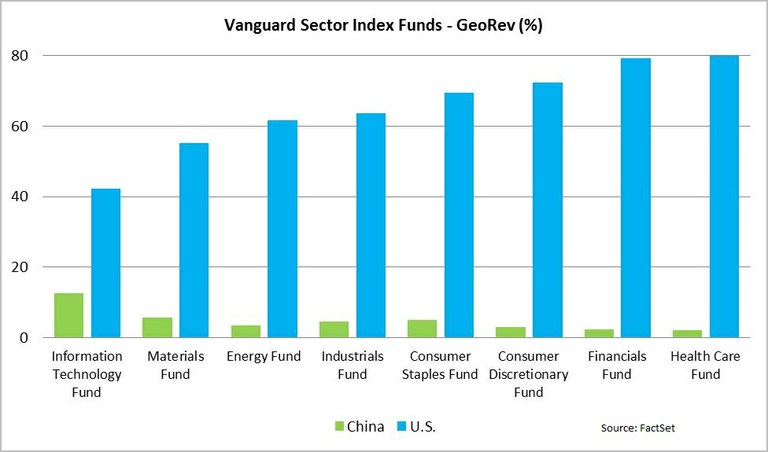

Knowledge on the revenue base of sectors and industries provides even more insight. Revenue is primarily generated domestically in the Utilities and Telecom Services sectors of the U.S., but approximately 40% of all revenue in the Information Technology sector is derived within the border. In that sector, China accounts for nearly 13% of market share and has grown over 200% in the S&P 500 index over 10 years.

Whatever the investment strategy, an increasingly globalized economy demands more sophisticated analytical tools. Economic data is useful in this regard, but it’s important not to skip the basic questions that focus and provide context to the economics. “Where?” and “to what extent?”: simple questions that no longer require complicated answers.