In a previous insight article, we discussed the fact that the Alternative Reference Rate Committee (ARRC) chose the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) as the replacement for USD LIBOR. In April of 2018, the NY Fed began officially reporting this rate, and the market started observing its dynamics. SOFR is a volume weighted median of tri-party repo transactions. Since it is determined by market transactions, the rate is affected by supply and demand, which is driven by daily bank operations and bank intervention. The overnight repo market is especially active at month and quarter end. This effect, called the “turn”, is well known in money markets.

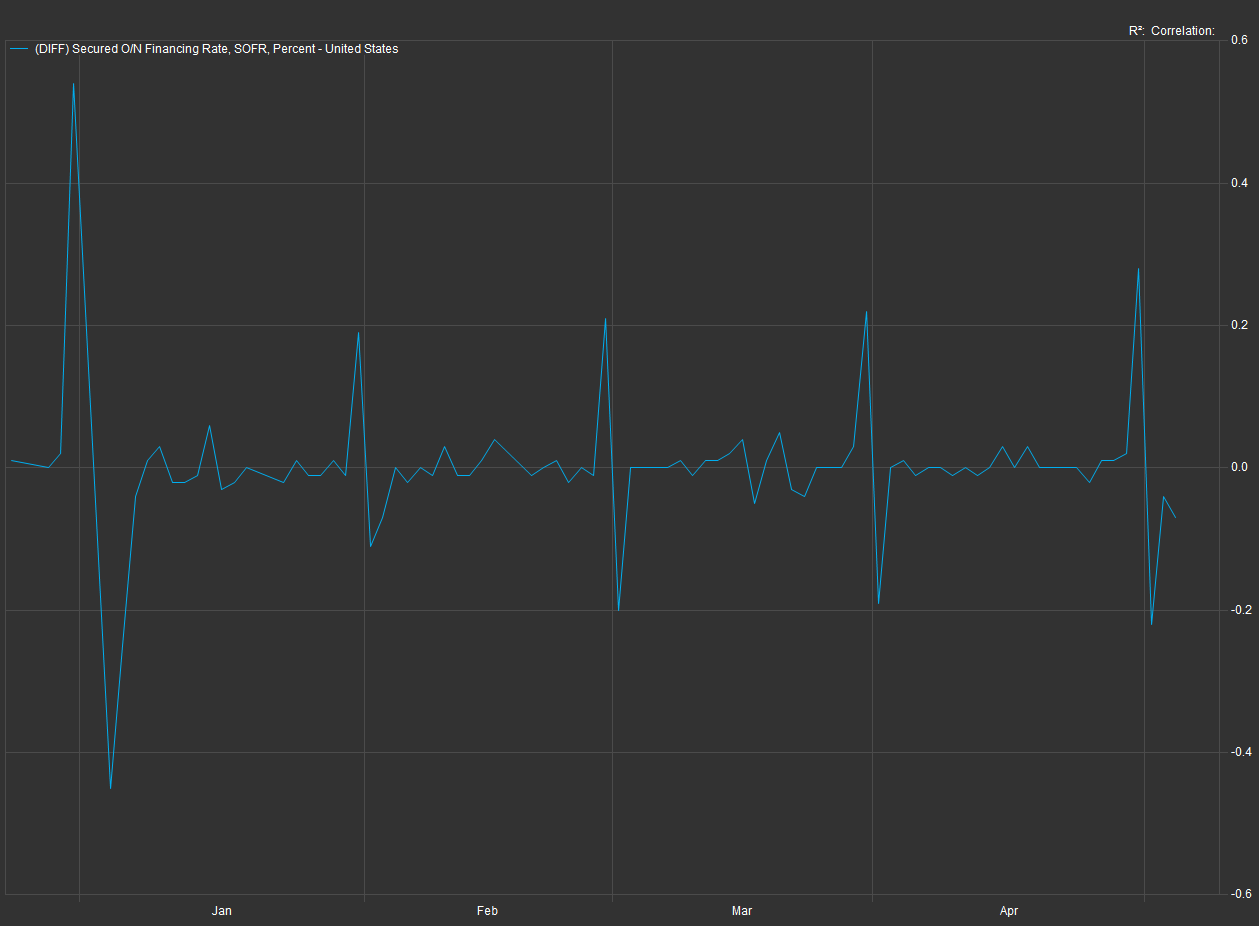

However September came and went with no appreciable move in the SOFR rate. Then January came in like a lion—with a two-day 65bp jump in the rate. The following four months’ end also showed this effect, with an average of a 23bp jump occurring precisely on the month end data. If we examine the day-over-day changes between January and May 2019 we can see why this effect was called “the heartbeat”:

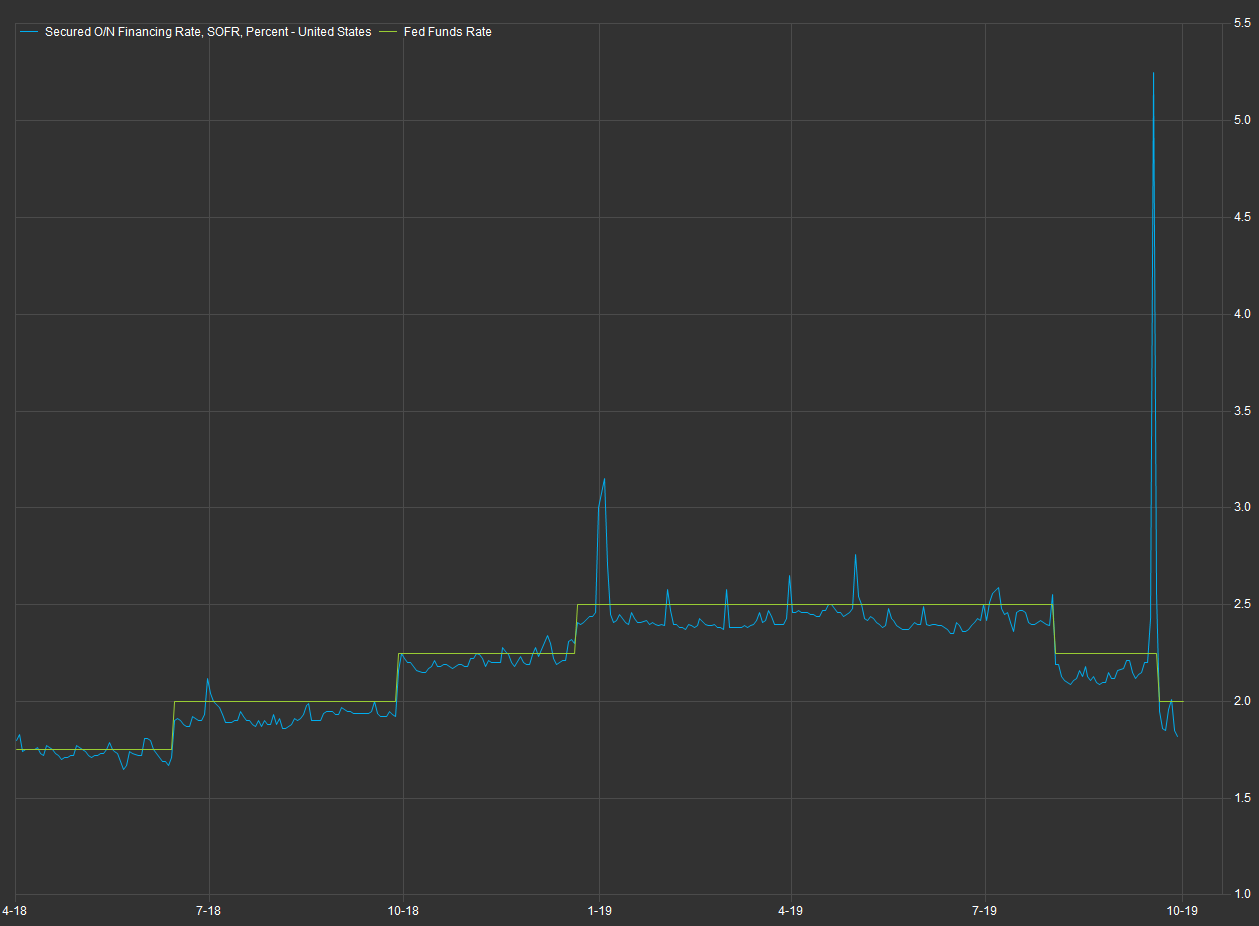

Then there were the ides of September. On September 17, 2019 SOFR swung by 282bp in a single day.

Why did this happen? According to Joshua W. Thompson, Patrick Clancy, Thomas Donegan, Lisa L. Jacobs and Donna M. Parisi from the firm Shearman & Sterling:

“The confluence of a number of events has exposed insufficient elasticity in the USD overnight cash repo market. Contributing to the stress on the system is an upcoming corporate tax payment date, which pulled cash out of the money market system, whilst at around the same time $115 billion of investment grade debt was being issued and traded (based on data for the first half of September). The secondary market trading volumes of this newly issued investment-grade paper increased inventories at broker dealers; who, in turn, rely on the repo market to fund those volumes. In addition, $60 billion of Treasury bond maturities negatively impacted available cash. All these events contributed to a cash crunch on September 17, 2019, that we refer to here as the ‘SOFR Surge Event’, in which the SOFR rate increased by 282 basis points, compared with the previous day.”

This behavior is problematic for the market for (at least) two reasons. The first is a consequence of the intended use of SOFR as the replacement for the average rate of top tier interbank lending. Swaps trade for a variety of reasons, including speculation on interest rates, hedging interest rate risk, to match liabilities, and to convert debt from floating to fixed (or vice versa). Switching the rate from an indicator of intrabank lending to a different market with different drivers and dynamics poses a kind of “dislocation risk”. Being a forward-lending rate, when LIBOR increases it does so smoothly and in response to dynamics in the intrabank market (LIBOR fixing notwithstanding). The overnight market, however, is extremely jumpy, and those jumps correspond to extraneous events like balance sheet reporting, debt issuance, etc. As SOFR is a backwards-looking rate, the coupon payment is set in arrears, which means that swap counterparties will be exposed to these jumps.

This first point is mitigated by the fact that SOFR swaps pay the compounded daily fixings, so one day of supply/demand disequilibrium reflects only one day out of the given term. In fact, the jump in the 90d trailing compounded SOFR rate on September 17th is of the same order of magnitude as the jump in the ICE-quoted three-month U.S. LIBOR rate on the same day—around 3bps.

The second point has to do with the short end of the treasury curve, which is notoriously difficult to construct. The first obvious choice are bonds with less than two years of maturity left, but as the Bank of Canada points out:

Choosing the appropriate data for modelling the short-end of the curve is difficult. Canada bonds with short terms to maturity (i.e., roughly less than two years) often trade at yields that differ substantially from treasury bills with comparable maturities. This is largely due to the significant stripping of many of these bonds, which were initially issued as 10- or 20-year bonds with relatively high coupons leading to substantial liquidity differences between short-term bonds and treasury bills. From a market perspective, these bond observations are somewhat problematic due to their heterogeneity in terms of coupons (with the associated coupon effects) and liquidity levels.

The next obvious choice is a t-bill rate, which is the path that the Bank of Canada ultimately took. However, the U.S. Treasury states:

Currently, we fit separate yield curves for bills and coupon securities. We do not consider this to be an entirely satisfactory situation. The practice began because we were fitting the yield curve to measure deviations from the yield curve largely for coupon securities, and we noticed that coupon securities with less than one year to maturity were priced measurably differently from bills. This difference may be driven by liquidity, taxes, or other effects.

In a sense, the repo rate is the perfect rate to anchor the curve, as it represents the one-day yield that can be obtained by lending bonds. However, the effect of the turn (described above) makes this a problematic choice, and would lead to an overstated volatility of the short end, as well as unstable analytics for short-term securities. This could be mitigated by using a historically averaged SOFR, or the first SOFR future to construct the short end of the curve.

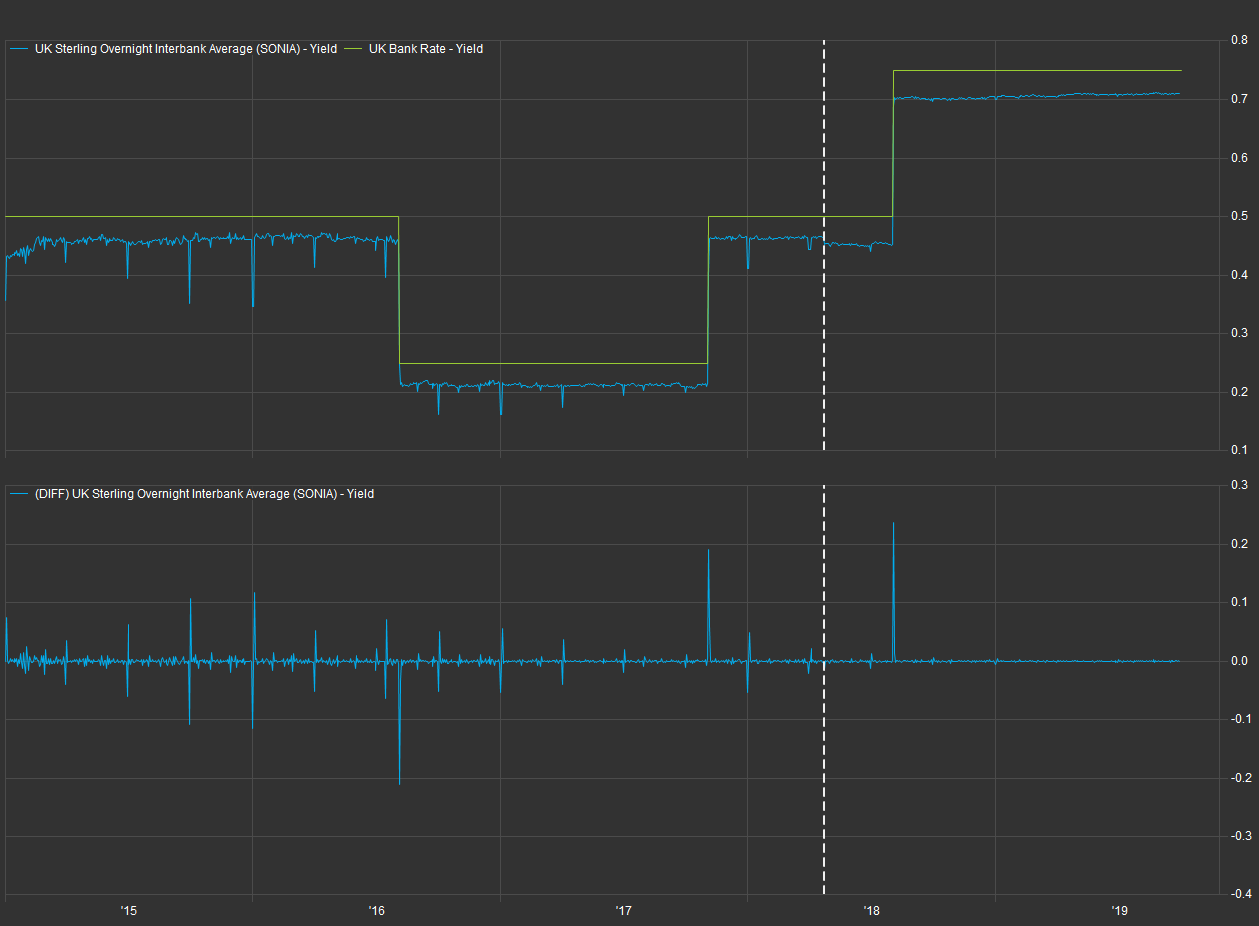

In the UK, the Bank of England (BoE) chose the Sterling Overnight Index Average (SONIA), the equivalent of the U.S. Fed Funds, as their LIBOR replacement. In their case, the SONIA also had this behavior, and the BoE took corrective measures to remove the problematic jumps.

The SONIA reform took place on April 23, 2018, marked by a white vertical line in the above chart. Clearly the reforms were successful: the only jumps appear when the BoE changed their target rate. At this point in time, the ARRC is not considering implementing any such reforms.

Is the market going to make the move?

Given the above issues with SOFR, are we confident that the market will adopt the change? The answer is yes, mainly because of the decision by the swap central counterparties (CCPs), the London Clearing House, and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. Both CCPs will begin discounting their swaps with SOFR in mid-to-late 2020. This requires all market participants to at least have the capability to use SOFR as a discount curve. If you discount with a swap curve, you have exposure to those swaps. This means the decision made by the CCPs will force top tier banks to begin trading SOFR swaps, leading the liquidity of the SOFR swap market to increase. Therefore, the SOFR term structure can be reliably built. Furthermore, the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) will publish the amendment on the fallback methodology in early 2020. There is a very high expectation that the derivatives market will quickly make the move to SOFR instruments beginning in Q2 of 2020.

Additionally, the SEC has stated quite strongly that market participants should be proactive in preparing for this transition. In a press release dated July 12, 2019 they state:

While not all issues related to alternative reference rates have been resolved, the Commission staff encourages market participants who have not already done so to begin managing their transition away from LIBOR. For many market participants, waiting until all open questions have been answered to begin this important work likely could prove to be too late to accomplish the challenging task required.

What happens to current contracts?

The LIBOR transition does not only affect swaps and derivative markets. There are many different types of contracts that will be affected by this transition as well: mortgages, asset backed securities, loans, floating rate bonds, and preferred shares. What happens to the contracts that were initiated before the LIBOR transition was even conceived? To address the behavior of such contracts, the ARRC and ISDA have been working together on “fallback language”.

The details of the fallback were chosen as a result of years’ long outreach and consultation with market participants. The conclusion is that in the absence of LIBOR, the rate will be set in arrears by compounding the daily SOFR rate during the entire coupon period. As SOFR is a risk-free rate, and LIBOR contains the credit of the tier one interbank market, the compounded SOFR will be less than LIBOR. Hence, a spread will be added, where the spread is determined by ISDA by using the average spread between the LIBOR and SOFR over a very long baseline.

The fallback language will differ for each asset type (derivatives, loan, mortgages, etc.). This could potentially trigger hedge mismatch and basis risk among different assets. In fact, the ARM market has decided to use the forward-looking SOFR average, as opposed to the backward-looking chosen in the derivatives market. The AARC states in its 2019 whitepaper “Options for Using SOFR in Adjustable Rate Mortgages”:

Although other products such as derivatives and floating-rate debt are gravitating toward the use of SOFR in arrears, the Working Group did not view this as appropriate for consumer products or consistent with consumer regulations because it would give consumers very short notice of payment changes and challenge servicers in meeting notice requirements for the notice of payment to be applied to consumer ARMs. Instead, the Working Group considered in advance as the most appropriate mechanism, given that: advance certainty of payment due from borrower to (lender) investor is critical for consumers, current regulations stipulate that a “change of interest rate” be furnished to borrower in advance of such change, and it is simpler to implement across the existing systems infrastructure for consumer ARMs.

Will LIBOR still be quoted after December 2021?

The ICE Benchmark Association (IBA) has indicated it will continue to publish LIBOR after the end of 2021, however with cautionary words around the effective use of a discontinued benchmark. They’ve said “users of LIBOR should not rely on the continued publication of any LIBOR settings when developing transition or fall back plans.” This is very similar to the caution of Andrew Baily, CEO of the Financial Conduct Authority, who said “…fall backs are not designed, and should not be relied upon, as the primary mechanism for transition. The wise driver steers a course to avoid a crash rather than relying on a seatbelt.”

Even if the IBA still conducts the poll, if there is no requirement for banks to respond, it is unlikely that all 11-16 of the contributing banks will continue to do so. Even if they do, over time likely some will cease, and at unknowable dates. This will result in a smaller sample size. In fact the LIBOR rules dictate that if an economy dependent minimum of banks do not respond, then LIBOR cannot be quoted. There is a real possibility of degradation of the quality of LIBOR post 2021.

The main conclusion is that, at this point in time, every firm should be executing on their LIBOR transition plans in order to have the system in place for the LCH and CME switchover in mid-2020.

What to do right now

Although the market trading activities are picking up (especially after the recent spikes) the market instruments associated with SOFR are still relatively illiquid (however, note that on the day of the spike, the notional value of the SOFR futures surpassed 1 trillion USD).To prepare, there are several things firms can do right now:

- Construct the SOFR curve

The market in swaps is growing; currently there is liquidity out to 2y and this data is available from interbroker dealers. However, the liquidity is moving out further along the term structure, precisely due to the announced changeover from the central counterparties. Lacking this data, the short end SOFR curve can be built from SOFR futures, and the longer end SOFR curve can be built by assuming a constant spread between SOFR and Fed Funds or SOFR and LIBOR.

- Construct SOFR vol cube

Currently there are no traded SOFR options. If the market truly believes that LIBOR will disappear, the current LIBOR trades that extend past 2021 will be converted to compounded SOFR set in arrears plus a spread. As the ISDA Fallback spread will be constant, the volatility of SOFR would be same as volatility of LIBOR, which means current LIBOR volatility cube instruments (swaptions, caps, floors) can be used to build SOFR vol cube[1].

- Price SOFR instruments

Make sure the pricing libraries can handle the multi-curve framework, as LIBOR and SOFR will coexist at least for the time period between the CCP switchover (mid 2020) and the end of the obligation to participate in the LIBOR poll (end of 2021).

[1] This was pointed out by Fabio Mercurio at a recent SOFR conference in New York City.