In January, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of Japan (BoJ) left their quantitative easing programs in place and policy rates unchanged at their scheduled meetings. Similarly, both the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England (BoE) maintained monetary policy stances at their respective meetings earlier this month.

FactSet clients: launch this chart

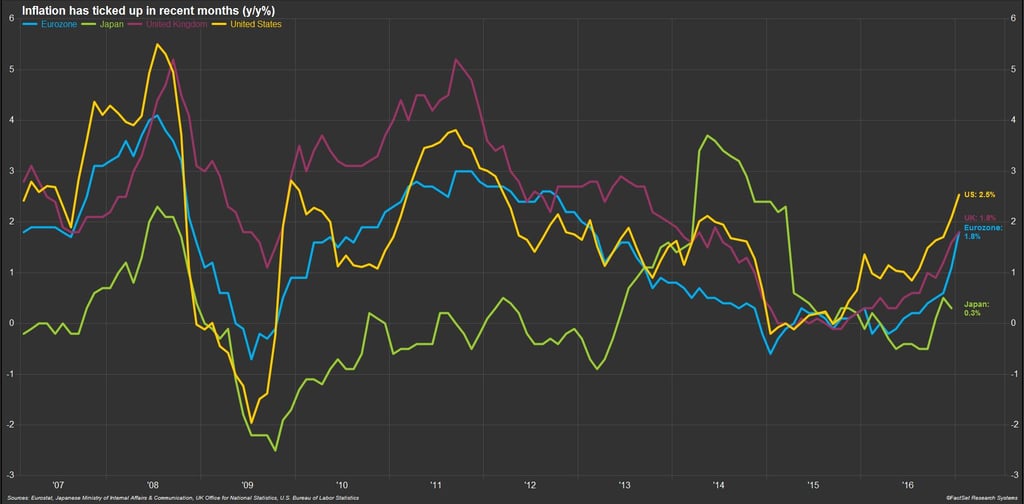

Since the global financial crisis, historically low inflation and restrained economic growth has allowed central banks to keep interest rates at record low levels. However, most policy makers are anxious to return to a more “normal” environment where they have more latitude to tighten or loosen monetary policy. Even though they kept policy on hold for now, each of these four central banks is anticipating higher inflation ahead, although it isn’t clear how quickly they will start raising rates.

Bank of Japan

In Japan, after years of price deflation, the prospect of inflation is welcome. The overall consumer price index slipped by 0.1% in 2016, while the core index (excluding volatile fresh food prices) dipped by 0.3%. In its latest outlook publication, the BoJ indicated a positive shift in its inflation and growth forecasts due to rising commodity prices, a weak yen, and improvements in both domestic and overseas economic activity.

The prospect of a weak yen is key to boosting prices and economic growth. A weak yen makes imports more expensive, pushing up domestic price levels, but it also makes exports cheaper, helping exporters and boosting overall GDP growth. Higher prices at home have the potential to negatively impact personal consumption, but the BoJ is optimistic that tight labor markets will lead to higher wages, further stimulating inflation while also boosting incomes. With an inflation target of 2%, it will be some time before the BoJ will actually need to tighten monetary policy.

Bank of England

This week the United Kingdom released statistics showing that consumer price inflation reached a 2.5-year high in January. The 1.8% year-over-year increase is still below the BoE’s stated inflation target of 2%, but the trend points to continued upward price pressures due to the sharply weaker pound in the wake of the Brexit vote in June 2016. The BoE’s most recent Monetary Policy Summary indicates that the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) is fine with allowing inflation to edge above the target stating that, “inflation is expected to increase to 2.8% in the first half of 2018, before falling back gradually to 2.4% in three years’ time. Inflation is judged to return to close to the target over the subsequent year.”

The MPC goes on to say the weaker pound is part of the adjustment to “new international trading arrangements,” and that attempting to fully offset the impacts of the weaker pound could have adverse effects on economic growth. However, there is a risk that higher-than-expected wage growth could force the MPC to raise rates faster than expected.

European Central Bank

Growth is picking up in the eurozone but there are looming financial and political factors that will continue to put downward pressure on the euro. These include nervousness around upcoming elections in France, the Netherlands, and Germany (and possibly Italy), renewed talks with the International Monetary Fund regarding another Greek bailout or debt forgiveness, and the ongoing Italian banking crisis. The region as a whole grew by 1.7% last year, but the risk is that political uncertainty will depress consumer and business confidence in the coming months. By boosting exports, the weak euro will provide a buffer to the lack of domestic demand. Inflation has stayed at bay for the last two years; harmonized consumer price inflation came in at just 0.2% in 2016, on the heels of zero price growth in 2015. However, inflation picked up sharply in the last two months, with prices jumping 1.8% year-over-year in January and 1.1% in December. Even if this trend continues, it is highly unlikely that the ECB will be tightening monetary policy in 2017 under the cloud of the ongoing economic turmoil.

The Federal Reserve

Meanwhile in the United States, the Federal Reserve has already started to reverse course on interest rates. When it raised rates in December, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) indicated that it expected to make three more moves in 2017, and three more in both 2018 and 2019. In her testimony to Congress this week, FOMC chair Janet Yellen reiterated the committee’s hawkish stance, stating that, “waiting too long to remove accommodation would be unwise.” She also implied that a March rate hike is not out of the question. Fed funds rate futures still only have the likelihood of a March hike at 22% according to the CME Group, while odds of a June hike are 46%.

Inflation numbers released this week support the Fed’s concern. Producer prices rose 0.6% in January over the previous month, the fastest monthly increase since September 2012; consumer prices also saw a 0.6% monthly jump in January, the biggest increase for that measure since February 2013. Core inflation measures remain somewhat benign, but in the coming quarters, the FOMC expects wages to rise in response to tight labor markets and more general price inflation to result from accelerating economic growth.

FactSet clients: launch this chart

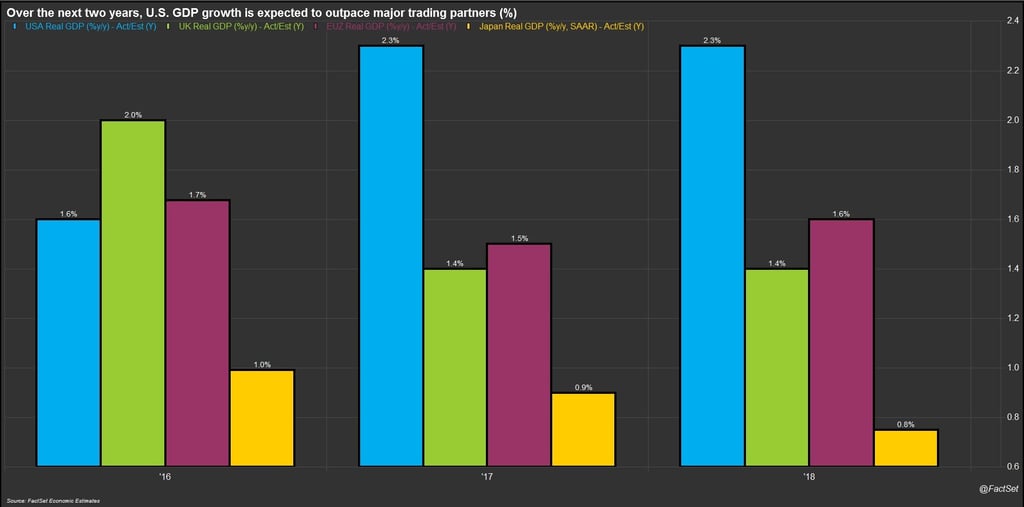

This expected acceleration of U.S. economic growth is increasing the perceived growth differentials between the U.S. and its key trading partners. The U.S. economy grew by 1.6% in 2016, outpacing Japan’s 1.0% increase but behind the UK’s 2.0% expansion and the eurozone’s 1.7% growth rate. However, the impact of Brexit is projected to drag down the UK economy in 2017 and the political and financial uncertainty in Europe discussed above is expected to depress eurozone growth. Growth forecasts for this year highlight this momentum shift; analysts surveyed by FactSet predict 2.3% GDP growth for the U.S. in 2017, compared to 0.9% for Japan, 1.5% for the eurozone, and 1.4% for the UK. This growth disparity is supporting a strong dollar as markets price in anticipated interest rate hikes.

FactSet clients: launch this chart

The Fed’s trade-weighted dollar index peaked at a 14-year high at the end of December, and although it has retreated slightly in recent weeks, the dollar remains strong by historical standards. The path of inflation is the biggest unknown in the global outlook, so it remains to be seen whether central banks will be aggressive in 2017 or if they can continue on their current path.