Special guest contributors from Axioma, Inc.

Dieter Vandenbussche, Ph.D., Senior Director, Research

Vishv Jeet, Ph.D., Sr. Associate, Research

Sebastian Ceria, Ph.D., CEO

Melissa Brown, CFA, Senior Director, Applied Research

More and more, asset owners and investment consultants require managers to report the active share of their portfolios. Active share is a metric that presumably measures how active a portfolio is. The underlying idea is that the closer a manager is to his or her benchmark, the smaller the degree of potential outperformance, and therefore the less likely that fees can be justified (or the more likely the manager is a "closet indexer"). But is active share the right measure for achieving this worthy objective? We will start by pointing out some of the measure's deficiencies, but our main goal is to show how various portfolio inputs – especially those common to quantitatively driven managers – impact active share.

But first, a quick review of active share. Active share measures the degree of deviation of aggregate portfolio weights from a benchmark. It is a single figure that is equal to half the sum of the absolute values of the active weights of the portfolio, which is equivalent to the sum of the positive active weights. A fully invested, long-only portfolio will have an active share that ranges from 0% (if the portfolio equals the benchmark) to 100% (meaning none of the assets in the portfolio is in the benchmark). The seminal paper on active share, How Active is Your Fund Manager? A New Measure That Predicts Performance, and its follow-ups set a somewhat arbitrary level of 60% as an indication the portfolio is "sufficiently" active.

Even without knowing anything about a manager's process, we can discern some problems with active share as a measure of potential outperformance:

- It doesn't capture the degree of a manager's conviction on any or all bets

- It doesn't measure how risky the bets are, i.e., it knows nothing about variances and covariances of the active holdings

- It doesn't see the true "activeness" for a manager taking factor bets

- It doesn't indicate how diversified a portfolio is

- And, finally, many small bets will yield the same active share as a few large bets

In addition to misread on factor bets, there are other issues with active share that can be a particular bane for quantitative managers who optimize their portfolios. There are at least four problems of which quantitative managers should be aware.

Alpha Scores

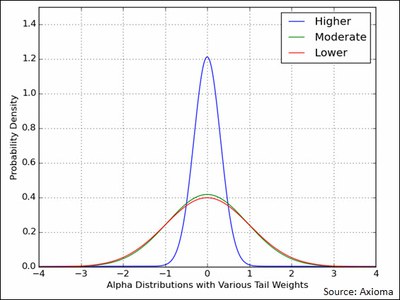

Different distributions of alpha scores will lead to different active shares, even for portfolios that have the same benchmark and targeted tracking error. Alphas with "fat tails" will reduce active share relative to less kurtotic ones and can also lead to more variable active share.

Figure 1. Higher kurtosis leads to lower average, as well as more variable, active share.

Size Bias

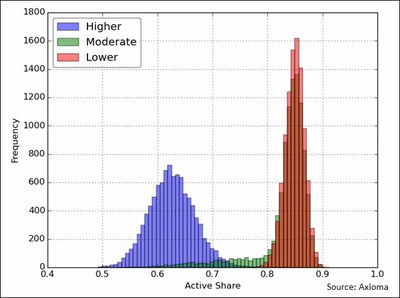

Optimized long-only portfolios will tend to have a small-cap bias, since smaller stocks can only be underweight up to their (small) benchmark weights. While any stock can be overweight as much as desired, the inability to take on big underweight positions impacts the overweights as well, and this affects active share. Axioma's experiments reveal that if alphas and size are positively correlated, active share will be lower, whereas a negative size tilt can lead to higher active share.

Figure 2. A positive correlation between alpha and size leads to lower active share.

Tracking Error

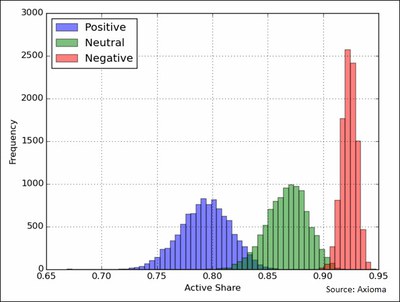

Many quantitatively driven managers target a specific level of tracking error. However, a manager may find that her information ratio is maximized at a relatively low level of tracking error – a desired outcome – but that low tracking error means low active share. She may be forced to increase tracking error, which could lower the efficiency of the portfolio or, alternately, be deemed not active enough when, in fact, her portfolio is run at optimal efficiency, and could be levered up to achieve a higher return if necessary. In addition, for a given tracking error, active share can range widely over time. In times of high market volatility and/or high correlation, an optimizer will choose smaller bets to avoid exceeding the tracking error target, thus lowering the active share.

Figure 3. Active share varies over time for a given tracking error, and at a point in time higher tracking error means higher active share.

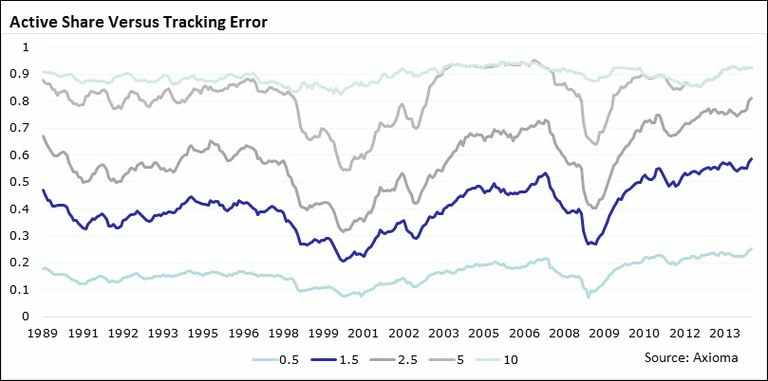

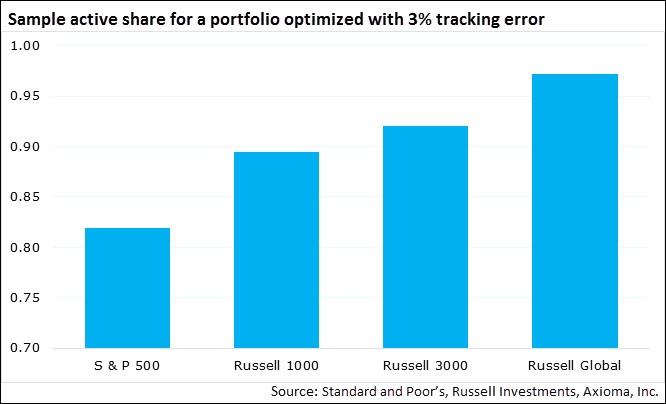

Benchmark Selection

Finally, choice of benchmark can have a big impact on active share. A concentrated benchmark means the manager will be unable to have big underweight positions in most of the component stocks, save the few with big weights. This, in turn, affects the manager's ability to overweight stocks. Similar to the small-cap-bias issue mentioned above, this means that it is much more difficult to achieve a high active share with a more concentrated benchmark. Of course, the manager often does not get to choose the benchmark. And note that this impacts all managers, not just quantitatively driven ones.

Figure 4. The more concentrated a benchmark, the lower the active share.

Active share is a simple metric that measures what percent of a portfolio is invested differently from the benchmark. It is a relatively new but a popular measure that asset owners are increasingly requiring managers to report. In some cases, asset owners are using the metric as part of their investment decisions. For all the reasons cited above, we believe that while active share can give some indication of the level of a portfolio's activeness, it should be used as a complement to other measures, such as tracking error and specific risk, rather than as a single measure to determine whether a manager is active enough. Too many factors have an impact on active share to allow it to be the single measure of whether managers are earning their fees.