Arguably the king of equity attribution is the Brinson-Fachler attribution model, and the most common question around the model is what to do with interaction? Allocation and selection stand alone and can be easily explained to an investor. Interaction, however, presents a trickier problem.

Allocation measures how well the manager weighted groups relative to the benchmark. Selection deals with how well the manager picked stocks vs. the benchmark. But interaction is where questions start to arise. Explanations like “strength of manager’s conviction,” “putting your money where your mouth is,” and “the interaction of both allocation and selection,” are a few explanations for interaction, but leave plenty to be desired. This in turn leads to the controversial question of what to do with interaction. And the answer is as frustrating as the questions; it depends.

Two-Factor vs. Three-Factor Attribution

Many fund managers choose to report externally with the two-factor model, combining the interaction into selection effect. The math works.

When you calculate selection effect with interaction combined you get:

(wip) * (Rip – Rib)1.

Where:

(wip) = Group portfolio weight period I

Rip = Return of the portfolio group period i

Rib = Return of the benchmark group period i

The active weight for the group in the portfolio is the multiplier for the excess return at the group level, which fundamentally makes sense. The manager picked those stocks, which resulted in a higher weight in that group, so the portfolio weight should be used to calculate the selection effect. For an external audience this seems sufficient and helps show the benefit of active management. In a world where passive is the new black, any analysis that highlights the benefits of active management is well received.

But internally at firms, what should fund managers and performance teams do? Looking at interaction for internal consumption can uncover valuable insight in the portfolio using both standard groupings that are reported externally (sector and country, most commonly) and using additional metrics to group the portfolio, such as market cap, dividend yield, or custom themes. The separation of interaction in these examples can tell a compelling story and help the manager understand where there maybe unknown biases in the portfolio or opportunity to increase alpha.

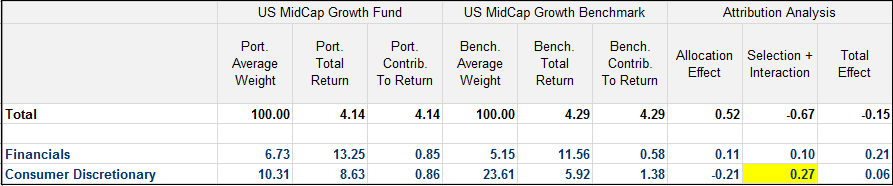

In the below example, the manager is credited with 27 basis points of Selection Effect within Consumer Discretionary in the two-factor model. She picked good stocks within Consumer Discretionary, contributing to 6 basis points of outperformance relative to the benchmark.

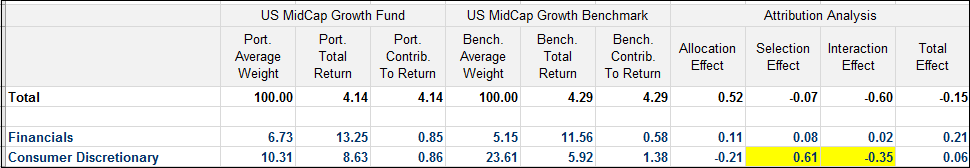

However, three-factor tells a different story. The manager had strong Selection Effect, 61 basis point. In the three-factor model the large benchmark weight in Consumer Discretionary inflates the security selection to this 61 bps. Since the manager underweighted a sector (negative active weight) and picked stocks that outperformed compared to the benchmark (positive alpha), the interaction effect hurts the portfolio.

By separating out the interaction effect, the analysis reveals opportunities to recalibrate the strategy. For example, here the manager may want to think about increasing her weight to Consumer Discretionary, since it is largely underweighted and she looks to have superior stock selection in this sector compared to the benchmark. This insight easily goes unnoticed in the two-factor model.

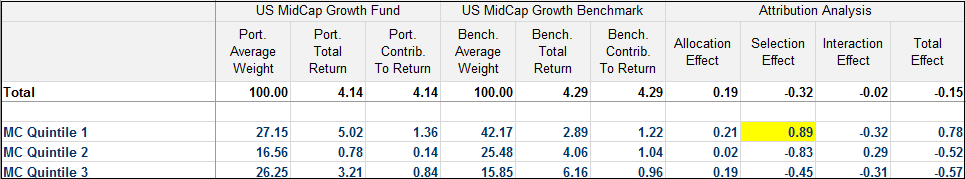

Expanding the groupings outside of the traditional sector and country, we uncover additional insights. Continuing with the same example portfolio from above, the manager had strong stock selection in the largest cap securities within MidCap Growth but struggled in other market cap ranges. An unhidden bias to the larger cap securities within the portfolio? Maybe. Worth digging into further? Absolutely.

By working together to gain a deeper understanding of what metrics are driving performance the fund manager and the performance team can uncover valuable insight to the fund’s performance. So interaction isn’t just the third effect in the Brinson-Fachler model; it’s also a key component of the investment process.

Productive and meaningful interaction between the fund manager and performance team is not just important, it’s an art.